I was studying for an undergraduate music history exam when I fell asleep on the floor. A boombox rested beside me and a local jazz radio station, WBGO, was playing. I was shocked from my slumber as I exclaimed, “What the hell was that?” Perhaps, if I was fully conscious, I would have provided a more eloquent response. The issue wasn’t what was that, but who was that. The answer was…Bill Evans. The album was Everybody Digs Bill Evans and the tune was the sublime, yet earth-shattering, “Peace Piece.” This was my discovery of Bill Evans and I knew, from that point forward, I needed to learn everything possible about him and his music.

In the Fall of 2001, I entered the Master of Arts program at Rutgers University for Jazz History and Research. Admittedly, as an undergraduate at Rutgers who studied classical music history and theory, I had a scant knowledge of jazz and the cultural capital put forth by the African American community. This would change immediately as I was hurled into the deep waters of the slave songs: the field hollers, the work songs, and the spirituals.

So, as Eugene Holley posited in his astute article, “My Bill Evans Problem: Jaded Visions of Jazz and Race” from 2013, “What was the problem?” For Holley, it was his internal reconciliation with being a black man who was drawn to the music, “It was Bill Evans’s love of, and application of, European classical styles, approaches, and motifs into jazz that was so attractive to my ears, as evidenced by the…intoxicating melodicism of “Israel” from Explorations.” For me, I quickly realized that as a young, middle-class, white man, I knew very little of the historical underpinnings that made jazz possible.

Over the course my graduate education, my sense of conflict fostered an inherent embarrassment. How could I champion someone who looked like me and herald him as the most profound musical influence of my life? What about Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, or countless other masters of this black, American musical tradition? It didn’t matter that the cover of Everybody Digs Bill Evans was replete with affirmations from jazz icons such as Miles Davis, “I’ve sure learned a lot of Bill Evans. He plays the piano the way it should be played.” I still wrestled with the notion that this music was born from the tainted fields of the antebellum South—far from the Rockwell-esque neighborhoods of Plainfield, New Jersey, where Bill Evans spent his formative years.

My “Haunted Heart,” a reference to Evans’s poignant rendition of the Arthur Schwartz tune, became more plagued when I took a class on “Jazz and Race” with my mentor, Lewis Porter. One objective of the course was to address the question, “Is Jazz Black Music?” I considered the implications of the query:

1. Did jazz belong to black people?

2. Is jazz performed by black people more authentic than that made by musicians of other ethnicities?

3. Is jazz a cultural consequence, with its roots inextricably bound to the African American experience, but can be shared and played by anyone?

I knew this would initiate a skirmish between my intellectual and visceral selves.

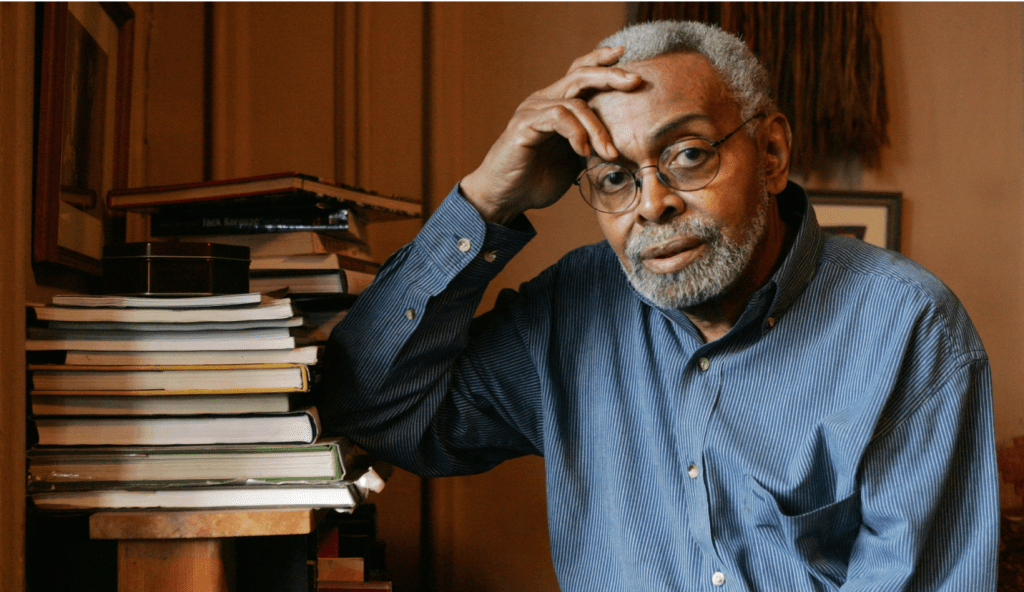

In a 2007 panel discussion at Jazz at Lincoln Center entitled Race in Jazz Academia, Amiri Baraka declared, “What does America have of value in the arts that it created except Afro- American music? Now the refusal to accept it as that—black music by black people, you understand, is no different from the status that we’re regarded in everything.” He continued, “I mean [white] people think that tap dancing started with Fred Astaire!” With this example, Baraka reminds people that black dancer, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson was the progenitor of tap dancing.

In 1963, Baraka, formerly LeRoi Jones, published a ground-breaking text on the role of race in the development of music in America. It was entitled, Blues People: Negro Music in White America. Regarding the origins of “Negro” music, he declared:

That there was a body of music that came to exist from a people who were brought to this side as slaves and that throughout that music’s development, it had had to survive, expand, reorganize, continue, and express itself, as the fragile property of powerless and oppressed [p]eople.

The “body of music,” to which Baraka was referring, were the slave songs and their expansion and reorganization ultimately fostered the developments of the blues and jazz.

By 1860, there were roughly four million Africans enslaved in the United States. Forcibly transplanted to a new land, they brought with them a rich, African heritage—including songs. Adapted to reflect the hardship of forced labor on plantations, field hollers, work songs, laments, and shouts of protests wafted through the air like the scent of smoldering sugar cane. Frederick Douglass captured the impulse behind these songs in his autobiography:

Slaves sing most when they are most unhappy. The songs of the slave represent the sorrows of his heart; and he is relieved by them, only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears. At least, such is my experience. I have often sung to drown my sorrow, but seldom to express my happiness. Crying for joy, and singing for joy, were alike uncommon to me while in the jaws of slavery. The singing of a man cast away upon a desolate island might be as appropriately considered as evidence of contentment and happiness, as the singing of a slave; the songs of the one and of the other are prompted by the same emotion.

The field holler was performed by a lone slave with the explicit function of self- expression—ways of communicating despondency, loneliness, lassitude, or any myriad human emotions. Conversely, the work song was practiced in groups and helped synchronize the slaves’ movements, lift their spirits, and, in general, help manage the toil of daily life of being captives in a free land. These songs, along with the spiritual, evolved into the blues—the wellspring that would feed the varied streams of vernacular, American music—including jazz.

The blues, as a musical form and a form of musical expression, was an advent of post- emancipation America; as such, it celebrated the possibility of freedom for the black population albeit within a world rife with uncertainty, racism, and oppression. The unique character of the blues projected dejection and despair, but as jazz saxophonist, Branford Marsalis declared, “The blues are about freedom. There is liberation in reality. When they talk about these songs…when they talk about being sad, the fact that you recognize that which pains you is a very freeing and liberating experience. When I hear the blues, the blues makes me smile.” The late writer and cultural critic, Albert Murray, concurred, “Playing the blues was a matter of getting rid of the blues. The lyrics may have been tragic in their orientation, but the music was about having a good time. So, the music was really a matter of stomping the blues away.”

Bill Evans was not a blues player. In fact, he considered the blues to be a very restrictive harmonic framework on which to improvise. Besides, how could a middle-class, white kid from the suburbs of New Jersey possibly relate to the horrific calamity that was systemic racism? Clearly, it was through empathy. And this characteristic, along with the fact that he, as Miles Davis exclaimed, “could play his ass off,” catapulted him into the spotlight in 1958 when the famed trumpeter was looking for a pianist to replace the unreliable Red Garland.

There are conflicting stories on the origin of their union, but according to Evans:

Finally, one day in 1958, Miles was on the other end of the phone asking me to make a weekend in Philadelphia, which was a thrill to me. I felt that band was, and perhaps still do, the greatest jazz band that ever was. And when I made the weekend in Philadelphia, he asked me to join the band and that was the tenure that I had with Miles at that time.

Miles was drawn to the introspective, laconic impressionism that Evans coxed from the piano. “Bill had this quiet fire that I loved on the piano. The way he approached it, the sound he got was like crystal notes or sparkling water cascading down from some clear waterfall.” That sound was developed through years of self-exploration. He humbly proclaimed to his friend Gene Lees, “I had to work harder at music than most cats, because you see, man, I don’t have very much talent…it’s true,” he said. “Everybody talks about my harmonic conception. I worked very hard at that because I didn’t have very good ears.”

That quiet fire, that harmonic conception, were the quintessence of Evans’s style. Just listen for the minimalistic pathos of “Blue in Green” from Davis’s epic Kind of Blue or the heart-breaking eulogy for his father, “Turn Out the Stars,” from the album, Bill Evans at Town Hall. Surely, any musician who can captivate millions of listeners, irrespective of their ethnicities, with such profoundly stirring melancholy and earn the respect of a jazz luminary as Miles Davis, must be worthy of being placed in the music’s canon and prove that jazz is not black music, right? Maybe not.

My haunted heart gained some clarity when listening to Baraka from the Jazz at Lincoln Center discussion:

But the people who play, like say, European concert music…there are several Negroes who play that and who can play it well, but you can remove them from that and it would not change the history of the music….I mean you could remove every black person, Japanese, Chinese, Indian, playin’ European concert music and it wouldn’t change the history of that music. As skilled as they would be…as great as they would be….you know, you could remove Yo-Yo Ma and it wouldn’t change the history of the European concert music. You understand? Because it’s coming from a particular place and a particular experience. Anybody can play it – just like anybody can play what they call jazz. But, it has particular history, a particular root, and like Sterling Brown said, “That’s your history up there.” Anybody can play it – it’s not magic…it’s not mystery. But to try to remove it from its origins, see, is a hostile act.

Baraka posits that the origins of the music and its foundation with the African American experience must be honored, “If you’re gonna play the music, you’re gonna learn about black people.” OK, I thought, as long as Bill Evans was respecting the tradition, he was playing black, American music. Viscerally, I was contented. But how can I intellectually discount the fact that the chord changes upon which most jazz musicians are improvising (save free jazz), are based on the Western European Common Practice period and the employment of functional harmony? Why can’t jazz, which can be considered among the most American of art forms, be seen as American, or as Murray espouses, “Omni-American”—a democratic union of variegated, cultural elements?

The answer lies within the confines of my haunted heart—a sense of guilt that I did not ask for nor did I earn. Perhaps, it’s not guilt. Maybe it’s a simple matter of conviction of expressing my empathy—a sense of compassion and humanity and an understanding that, as scholar Gina Dent has asserted, “You don’t have to be black to be a carrier of black culture.”

My internal turmoil is reconciled. Jazz is black, American music and all musicians who play it, irrespective of race or ethnicity, are vessels for its propagation.

Michael Conklin

Excellent article, Michael! Signed, another jazz blogger ❤

LikeLike

Thank you, Debbie!

LikeLike